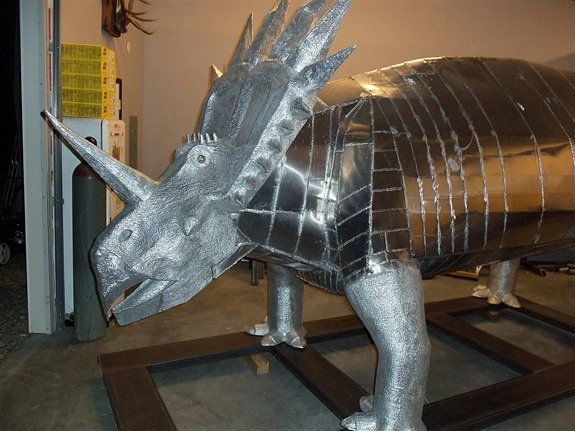

The Styracosaurus

AS BIG AS LIFE

Donated scrap metal sparked the inspiration behind seasoned fabricator and boilermaker Rick Kawchack’s aluminum dinosaur. “I took a bunch of aluminum racks and cut them up and thought they looked like a really cool dinosaur skeleton,” he says. It turned out the scrap metal had oxidized from sitting outside and was not weldable—first lesson learned—but the seed had been planted.

The boilermaker didn’t go straight from structures and rigs to large-scale metal sculptures. Kawchack has worked on several smaller artistic pieces, including aluminum crosses and 3-D modernistic art before deciding he wanted to switch to being a full-time artist. “It’s my passion and I have the skills needed to carry out my designs,” Kawchack says. Creating a full-size Styracosaurus—potentially 6 ft. tall and as long as 18 ft.—seemed like a great way to demonstrate his ability to produce larger works.

Based on his prior experience, Kawchack decided aluminum was the best material for the job. “If I made this out of steel, it would weigh 6,000 to 7,000 pounds,” he says. “That was a big reason to make it out of aluminum.” He knew welding aluminum would present challenges and he welcomed them. As a boilermaker, Kawchack frequently worked with high alloy steels in fire boxes, including stainless steels and Inconel. “Aluminum is cheaper than stainless, but not easier to work with,” he says. Among other things, Kawchack wore a respirator to avoid the toxic fumes emitted during the welding process.

After unsuccessful attempts to procure sponsors from nearby fabrication and weld supply companies, Kawchack took on investment in the project himself. “The only way I could make this name for myself was to actually produce and say, ‘Look what I did’—not ‘look at what I want to do.’” He built the shop and purchased the equipment and materials he needed to get started. Ultimately, he put in more than 2,000 hours on the project.

The dinosaur’s size and stature didn’t intimidate Kawchack, who is familiar with working on large structures weighing hundreds of tons. His experience as a boilermaker also prepared him for the amount of preparation and planning required when creating such a complicated design. However, unlike fabricating projects based on detailed plans and specifications, crafting a realistic-looking dinosaur requires frequent on-site adjustments.

Kawchack used a planishing hammer to hand form 16 gauge aluminum for the head. He also used a rubber mallet to form objects around a piece of pipe. Heating the aluminum made it soft, pliable and easier to bend.

To form the body, he used aluminum cut into strips. “I did quite a bit with my plasma cutter for the 1/4 in. and 3/16 in.-thick pieces, but for the majority of the metal, I used a shear,” he explains. He purchased 4 ft. by 10 ft. sheets in 10 gauge, which is about 1/8 in. thick. Using his friend’s large shear, Kawchack was able to cut the sheets and use them as strips, making it easier to form. “There was a lot of sledgehammer work to shape things how I wanted and control distortion,” he adds.

Kawchack faced some challenges during the process. He found heat dissipated quickly. “It was tough to keep the metal hot, so I had to use tremendous amounts of voltage. As the dinosaur became larger, it was like welding on a radiator,” he says. “I changed my welding procedure multiple times until I didn’t have to do external preheating.”

He also faced cracks and distortion because of weld-related stresses throughout the texturing process. Beyond that, using abrasive cutters contaminated the weld zone. “When I moved to the cold carbide instead of the abrasive, the results were much better,” he says. “As the project went on, the amount of distortion was tremendous and extremely hard to control.” There was a manway at the bottom of the chest and after texturing began, Kawchack went through the manway and reinforced the structure from the inside to control distortion.

“When you weld on one side, the other side wants to push out. I started at the bottom for the overlay process and worked my way up. Every pass worked up to control overall distortion,” he says, noting he knew he’d lose diameter during the process but didn’t know it would be as much as 3 ft. “I couldn’t know the amount of shrinkage beforehand. It was a back and forth process.” He controlled some of the distortion by annealing a lot of the material to relieve stress. As the metal heaved and even caved in some areas, he found he either had to dent the material or fill it back up.

The completed creature has more than 1.5 million spot welds and more than 800 lbs. of weld metal, leaving no question that Kawchack knows what he’s doing. The 2,000-lb. plus Styracosaurus is now for sale. If it is destined to stand outdoors, Kawchack says he will treat the aluminum to prevent oxidation, as well as allow for easy repairs should the need arise.

Having made the jump to large-scale art projects, Kawchack reflects on the learning experience: “It’s a lot more work than I thought it would be. It takes some big artistic ability and is probably not something the average person would want to consider because of the initial investment. I had to be confident in my abilities.”

970-629-2331

CRAIG, COLORADO

Shop Hours

Mon-fri: 8am-5pm

All Rights Reserved | Kawchack Metal Arts